|

WCC > Home > News & media > Features | ||||

| About the assembly | Programme | Theme & issues | News & media | |||||

|

|

||||

|

22.02.06

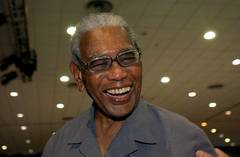

Philip Potter, an ecumenical pioneer

by Keith Clements (*)

More articles and free photos at

Philip Potter has a unique place in the modern ecumenical story. Not only was he general secretary of the WCC for 12 years (1972-84) but he also has the rare distinction of having attended all nine WCC Assemblies to date, beginning with the inaugural one in Amsterdam in 1948. Now in his 85th year, he can still recall vividly his early childhood on the Caribbean island of Dominica, his activity in the SCM in the West Indies - and that first WCC Assembly that he attended as a youth delegate.

"It was a great moment for us," he says. "It was the first gathering of the church, the first big event, after the war. Churches had been on both sides of the conflict. I had come to Europe in 1947 to complete my studies in London at Richmond Methodist College. Then there was a world youth conference in Oslo in 1947.

"I was already known to Wim Visser 't Hooft, the first general secretary of the WCC, through the SCM and WSCF. And here in Amsterdam were people who had been on both sides of the war. There were 100 of us youth delegates (50 men and 50 women). We constituted the choir! Then Visser 't Hooft asked me to address the Assembly on behalf of the youth. I spoke of our appreciation of being able to participate in this new relationship of churches."

At that time Philip Potter had no idea or dream that one day he would be the third general secretary of the WCC. After his studies he stayed in England, on the staff of the SCM, and then went to Haiti as pastor for four years.

" It was very hard there. I was a bachelor living on my own in the manse. There was great poverty, and getting around was difficult. I had no car or jeep and had to cycle everywhere. One of my best friends was a neighbour's dog. One day I fell over and hurt myself when leaving a house I had been visiting, and the dog came up to me as I was lying on the ground and licked my face! To live among the poorest of the poor for four years was a most formative experience for me."

All this is punctuated with gentle laughter. In 1954 he went to Geneva to work in the WCC youth department, then in 1960 moved to London as secretary for West Africa and the West Indies in the Methodist Missionary Society. In 1967 came a return to Geneva to serve as director of the WCC division of world mission and evangelism. He succeeded Eugene Carson Blake as general secretary in 1972. His 12 years in the post saw the Council facing some of the most challenging world issues and developing its reputation as foremost in the fight against injustice and human rights abuse.

Potter recalls:

"It was a time when we were a very controversial body. We were tackling things people did not like. There were conflicts with churches and different institutions. But at the same time, the WCC began to be a body playing a really public role not just vis-à-vis the churches but also governments, internationally. For example, in detailing the atrocities being carried out by the Brazilian military government and documenting human rights violations. Then of course there was the Programme to Combat Racism (PCR) and the struggles against apartheid and colonial oppression in southern Africa. But there were all kinds of other developments too. For example relations with churches in Eastern Europe. It was important for them that we were with them. Often we had to approach the authorities. But there could be humour too, for example with some Russian bishops when we met the titular president of the Soviet Union. At first it was very formal, and the president said to me, How am I to address you?' I told him, Call me brother!' Then he asked me, And how will you address me?' so I told him Comrade!' We also had dealings with China and its churches led by Bishop K.H. Ting. But often we did not make these kinds of dealings with governments public."

One naturally wonders how someone facing such challenges could cope with the continual controversies and conflicts. His answer is revealingly simple but realistic, with no false dressing of piety:

"When I left school, I worked with a lawyer and the attorney general. So I had a very early experience of what the world was like! I learnt the importance of humour. It's never been my style to be very formal and serious. I prefer a natural style of staying human and humorous. In the tough years in regard to Eastern Europe that was very important. It was the same when dealing with big finance corporations and institutions in the battles over investment in South Africa and so on. Here again I think it was important to remain myself, and keep a very human style, to encourage a sense that even when dealing with people with whom you disagreed strongly you were all striving together for the good of the whole community. And I have a heritage that enabled me to do this. My grandmother came of aristocratic Irish stock. Her death when I was nine years old was the first tragedy of my life. But she used to tell me, Philip, always be a gentleman!'"

Philip Potter in later life can look back on many rewarding experiences. He has also been recognized in ways that might not have been expected when in the thick of the struggles. No fewer than nine honorary doctorates have come his way, the first from Hamburg and the latest from the University of Cape Town - a recognition of how much the ecumenical commitment to end apartheid owed to his leadership. But, he says, what really gave him pleasure was learning how Nelson Mandela when in prison heard that the churches of the world were with him and with all those suffering in the cause of freedom, and how much encouragement that brought them.

What of the ecumenical movement today? He talks rather nostalgically of something he thinks may have been lost at the level of church and ecumenical leadership - the close and friendly relationships that he had, for example, with Roman Catholics including Pope Paul VI and especially the short-lived Pope John Paul I who took a close personal interest in Philip when his first wife Doreen was close to death. "The personal aspect is always very important."

And how would he like to be remembered? "As an ordinary chap, even when we had very heavy fights on some issues - that I could remain human, that I could remain myself," he says, still chuckling.

[1126 words]

(*) Keith Clements, a UK Baptist minister, was general secretary of the Conference of European Churches 1997-2005.

Assembly website:www.wcc-assembly.info

Contact in Porto Alegre:+55 / 51 8419.2169

|

|||

|

|

|